Sitting in JFK, Terminal 4, waiting for my 17 hour adventure to Cape Town to begin! And also, to be honest, at this point I was really excited by anything I saw with the words ‘South Africa’ on it.

I. The Beginning

The sunrise was gently gorgeous, a pale, still, vibrant array of peaches and yellows, on the morning that I left for South Africa. It was a reminder, I thought, that there was so much beauty to be found in the present. I pointed it out to my friend (a saint who was driving me from my home in Philadelphia to JFK Airport in New York at 5 AM) and saved the visual to my mental photo library. This is my last American sunrise for 3 weeks, I thought giddily to myself. The next time I see a sunrise in America, I will be a different version of myself.

And I was right.

The following collection of thoughts seeks to delve into the idea of exploring and visiting museums as a form of self-edification and also as a vessel for emotional enlightenment. On a more personal level, this article also provides an account of one black American woman’s experiences in travel and in personal emotional growth.

In recent years I’ve become intrigued by the undiscussed histories of black people, or the people of the African Diaspora. As a teacher who prefers to work in cities, the majority of my students have been black and brown. Thus, my mission for the past few years has been to make sure they’re far more aware of some aspects (as it is impossible to teach all, especially when some histories remain hidden) of their history than my counterparts and I ever were. There’s incredible intangible importance in these babies knowing more about who they are and who they have been in this country.

I had never traveled outside of the country before, but I realized that travel was a key (albeit, a key of privilege), and I needed to use its value to educate my students in a more experiential and meaningful way. So, I researched and vision-boarded and crafted multiple ideas, but eventually decided to first take my interest in South Africa’s apartheid and compare it with the current curriculum I taught about the Civil Rights Movement.

I kept a South Africa mini-vision board on the wall in my bedroom for about a year prior to my trip. This silly little drawing kept me motivated and reminded me of my ultimate goal. The little houses behind “me” are the famous colorful beach houses of Muizenberg, South Africa (also, those are supposed to be mountains behind the houses...an artist I am not).

In April of 2018 I received a grant to research Apartheid and current race relations in South Africa. I used that grant to book a spot with a volunteer program which would provide meals, lodging, and an opportunity for me to teach in a school in a township (low-income areas which initially were spaces set aside during apartheid for black and colored people to live) outside of Cape Town. I set up a social media site for my students and their families to follow, and I continued researching as much as I could about South Africa’s general history as well as apartheid. One of the biggest questions I hoped to figure out was how something we as Americans had (allegedly) identified as wrong could actually transpire elsewhere, and so late in the 20th century. This was, after all, the question that consistently boggled the minds of my students during our discussions (“But why is racism still happening now?”).

I knew a few things going into my first travel abroad experience. I knew that, as much as I enjoyed my privacy and solitude, I would soon have none. Volunteers within the program I worked with stay in dormitory style housing, with bunk beds, shared bathrooms and shared kitchen/common space. I knew that most people who chose to do a volunteer program were between 18 and 25 years old. I, on the other hand, would be walking in as a 30-something professional elementary school teacher. Most importantly, I also knew that outside of my small American bubble, I knew nothing about other cultures and how they lived. I had nothing to lose but ignorance, right? So, in physically preparing myself for this trip, I knew to prepare myself for some potential social challenges as well.

What I was less prepared for was the toll that this trip would take on me emotionally. I had no thoughts of the psychological effects of viewing oppressive histories close-up—both positive and negative effects, certainly. I just hadn’t thought much about what was to be profoundly different—experiencing these museums and sites in person that I had only previewed online.

The very first thing I did after settling into my volunteer home was to take a trip with my housemates across the street (yes, the beach was right across the street from us!) to capture a photo in front of the actual beach houses of Muizenberg. It is really satisfying to draw (picture) yourself somewhere you’ve never been and then to actually go there.

II. Next

On one of my first days in the sparsely-decorated but cheerful classroom where I volunteered, the teacher, Linda (a wonderful human who became part-maternal figure/part-tour guide/part-mentor during my visit), asked her students if they would share with me any family stories they knew about apartheid and the removals (forced relocations of large numbers of people of color). Student after student stood up and shared tales from their family history about someone being severely mistreated due to skin color (mind you, they spoke mostly of their grandparents and even sometimes of their parents, because apartheid was that recent). A scholar whose family had immigrated to South Africa from Zimbabwe told a horrifying story of colorism (a prejudice within members of the same race where “lighter is better” when it comes to skin tone). I remember noticing that the students all spoke in an almost monotone manner.

It is a sin, I thought, for any of these 12 and 13 year olds to be able to speak so matter of factly about racism and to already encompass those familiar-to-me feelings of “less than” that come with it all. I struggled to look up during the stories. I stared at my shoes throughout most of them because I was deeply sad and uncomfortable. This, then, I thought to myself, was the bitter work I had chosen for myself by committing to the research of apartheid and racism in South Africa. This emotional rawness was what I hadn’t even thought to be prepared for, and I truly wasn’t. How could I be?

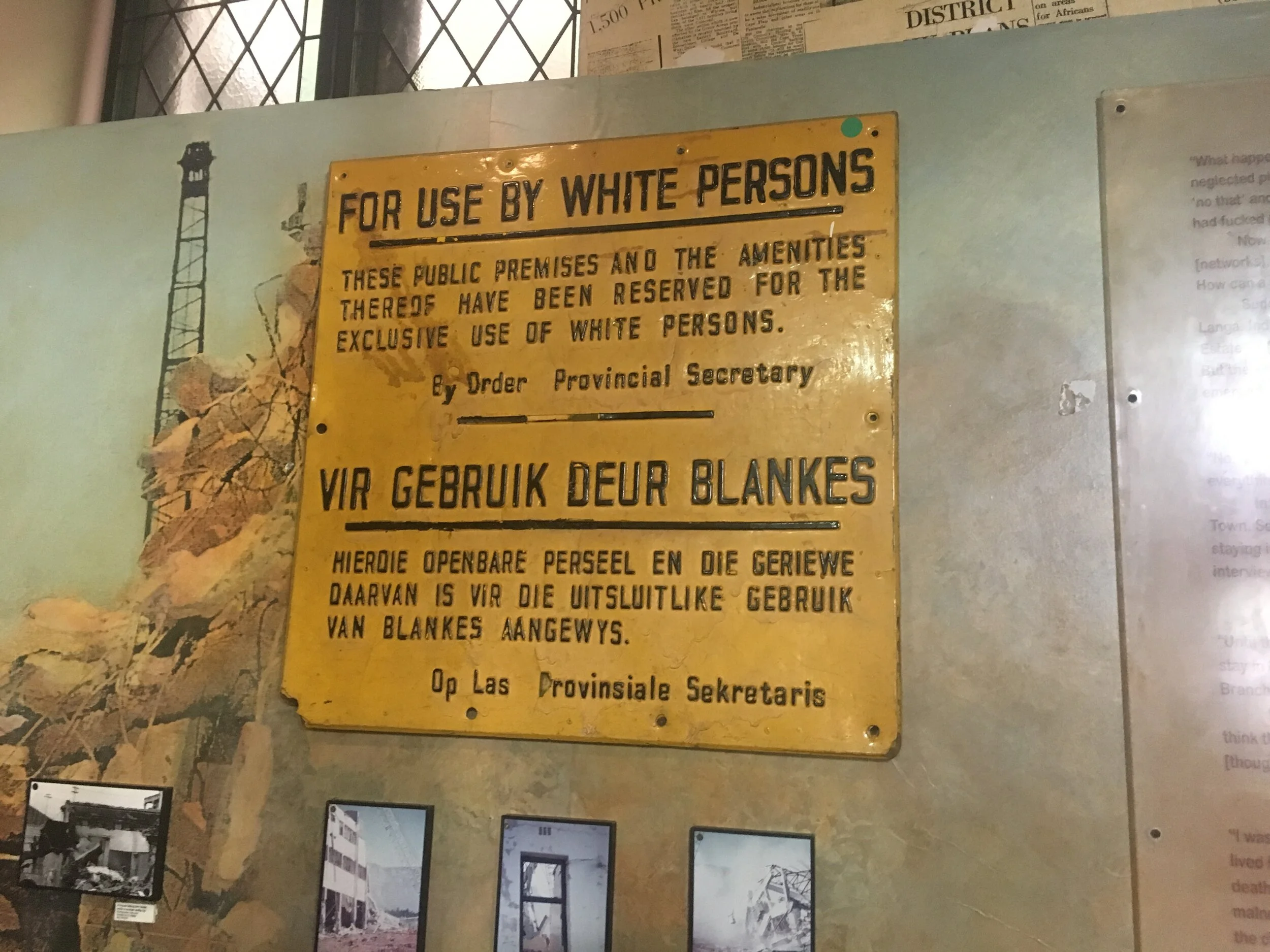

An apartheid artifact at the District Six Museum in Cape Town. I found this bench intriguing because there is such vileness in the idea of European settlers taking over parts of South Africa and declaring themselves South Africans, until it no longer suited them to do so.

Before I discuss my personal experiences at the museums in South Africa, it’s important to understand the actual purpose of a museum—meaning, for what reason do museums exist? My personal definition of a museum is something like: a facility which houses artifacts and information connected to a specific event or culture. I don’t remember ever learning a concrete definition for a museum—it was one of those words that I just always knew. Fortunately, there is the International Council of Museums (ICOM), an entity who, among other duties, is in charge of maintaining an accurate definition of a museum. In 2019, ICOM members decided a new definition of what a museum is and what purpose(s) a museum serves was needed. After months of discussion and collecting various definitions and proposals, the following was published in July 2019:

“Museums are democratising, inclusive and polyphonic spaces for critical dialogue about the pasts and the futures. Acknowledging and addressing the conflicts and challenges of the present, they hold artefacts and specimens in trust for society, safeguard diverse memories for future generations and guarantee equal rights and equal access to heritage for all people. Museums are not for profit. They are participatory and transparent, and work in active partnership with and for diverse communities to collect, preserve, research, interpret, exhibit, and enhance understandings of the world, aiming to contribute to human dignity and social justice, global equality and planetary wellbeing.”

* I’ve put the parts of the definition I find most relevant in bold.

To clarify, for all intents and purposes of this article, I am basically Team Museum. However, I do disagree with certain phrases within this definition. For example, for the most part, museums do require admission fees, which is completely understandable for upkeep, staffing, research, etc. This, however, limits patronage and is therefore not inclusive to all. People without the necessary admission money and reliable transportation (and money for that as well) will have a difficult time gaining access to these facilities. Let us also note: Not all museums “hold artefacts and specimens in trust.” Some have simply stolen a culture’s artifacts without consent and therefore, do not hold them in trust, but in blatant disrespect of other cultures. This can make trust a difficult concept for the very people museums supposedly hope to “work [with] in active partnership.”

Still, there are an awesome number of positive verbs connected to these establishments. Museums teach, they show, they share, they engage, they question, they teach us to question, they instill curiosity, ...and they can also do the opposite of all of these things if executed without the intent of pushing patrons to learn and change and grow.

When museums have really done their job and meant the most to me, I’ve experienced a visceral emotional reaction to the event or cultural object or idea being displayed. It takes something from my emotional energy bank that I need to let regenerate and heal. This was something I had experienced only once prior to my trip to South Africa, years ago at the Holocaust Museum in Washington, DC. Before South Africa, I had this overall notion of museums as dry, very traditional institutions of knowledge, and from most of my museum experiences, emotion didn’t fit into the picture. But I know now that emotion can be such an important part of a museum experience. I also now know that there’s a difference in intensity and depth of emotion when you experience these places alone. I highly recommend it, though perhaps not too frequently. It is heavy and burdensome to bear the weight of the monstrosities of history alone, and maybe a bit dangerous to hold all of that in, too. For my own part, I sunk into a depression for a while upon returning to America from South Africa. It was as if all of the emotional weight I was carrying with me was surrounding me in a bubble, and once I was home, the bubble burst.

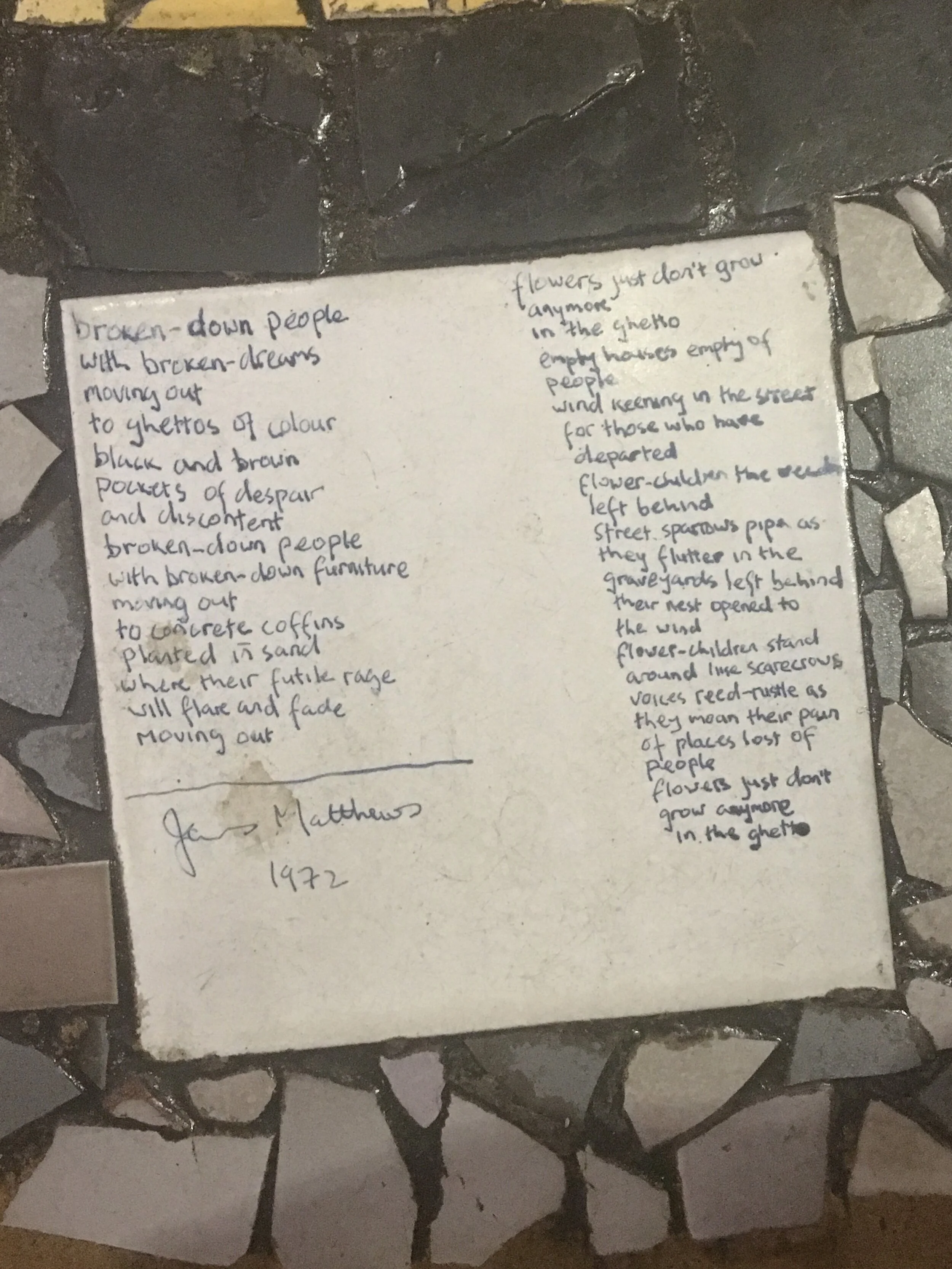

A beautiful example of the thought provocation museums can provide.

III. And Then

I barely glanced down at the entrance ticket my tour guide, Beth, had just placed in my upturned hand. My eyes were watching her retreating figure. “This is where I leave you,” she threw over her shoulder, with her bright smile and a wave. I grinned nervously and waved back as I looked around at the idyllic grounds. I bit my lip. Something about this place just felt different, already more intense. Butterflies swirled rapidly around in my stomach as I stood, all alone, on the sidewalk outside of the Apartheid Museum in Johannesburg, South Africa. I finally looked down at the ticket in my hand, and flinched. It read: “Blankes--Whites.” I proceeded to an entrance labeled exclusively for whites for the first time in my life.

The entrance to Robben Island, post-ferry ride.

I visited the following museums in South Africa to help with my research of apartheid: Robben Island, District 6 Museum, Mandela House, Apartheid Museum, and the Hector Pietersen Museum. My volunteer friends and I visited the first two museums in the Cape Town area, which were close enough to get to by Uber from our volunteer houses. A couple of weeks later, I went to Mandela House, Apartheid Museum, and the Hector Pietersen Museum alone, when I took my solo trip-within-a-trip to Johannesburg.

III. And Then

Museuming Together • Museuming Alone

Museuming Together

The wonderful thing about living and working with a group of volunteers is that not only is everyone kind and helpful by nature, but it’s very easy to find people who want to go out and explore together. There were several times when as many as 15 of us would meet up at a spot between our volunteer houses and head out together, sometimes splitting into micro groups somewhere along the way and then meeting back up for dinner and drinks later. Exploring together was nice on our pockets, because we were able to split the cost of our many Ubers. As we were all from outside of the country, there was a comfort and safety in numbers, because of course we were told that the city (and transit system, and surrounding townships, and basically any public area…) was a perilous place.

One significant group museuming trip for me was to Robben Island, the home of the prison where Nelson Mandela was held for 18 of his 27 prison years. According to its official website, “from 1961 to 1991, the apartheid government built a Maximum Security Prison on Robben Island which housed the political prisoners imprisoned there, who were fighting against apartheid and for freedom and democracy.”

At Robben Island. This is the rock quarry where Nelson Mandela and other freedom fighters worked. Deep inside, they tricked the prison guards by using an area as both their bathroom and their anti-apartheid movement meeting place. The guards, turned off by the smell, would not come close enough to hear what was discussed.

This site, an actual island that we had to access by ferry, was fascinating. Groups of us were shown around by tour guides, all former prisoners of Robben Island (I found it interesting that in South Africa, museums which show historical oppression are actually sometimes places of employment for the formerly oppressed or their descendants. I also noticed this at a plantation in South Carolina—but that is for a separate article, indeed). We visited the common areas of the prisoners where we were given oodles of information about the history of the freedom fighters imprisoned there and the various methods they implemented to get around the systems in place. We were also shown the prisoners’ cells, their outdoor “recreational” space, and the rock quarry where they were forced to work each day.

The prisoners’ courtyard on Robben Island. Behind me, where the foliage is planted, is where Mandela dug a hole and hid his first manuscript of A Long Walk To Freedom from the prison guards. He was eventually able to smuggle the manuscript out with a fellow prisoner.

This was the first museum/historical site I visited in South Africa, and a very positive museuming experience, especially where energy levels and emotional morale were concerned. I was with other academic-minded people who were content to let me linger, and wanted to help by taking photos for me whenever I needed. Visiting Mandela’s cell was emotionally challenging, if only for the sheer limited size of the space itself. Small rooms intended to oppress the already oppressed always affect me. So, we took photos and continued our tour, and I pushed the small cell out of my mind. We also spent a lot of time in the courtyard where prisoner plotting was monitored so it wouldn’t occur, but where Nelson Mandela hid a draft of the book that would become A Long Walk To Freedom, his legendary autobiography.

My time at Robben Island was a spectacular experience at a South African museum, and it was definitely beneficial to have my friends there to buffer the emotional blows. I also took extensive notes at this museum, which I think helped to keep me from thinking too much about the sometimes devastating information received from our tour guide. I came to the conclusion that, on one hand, being a part of this huge volunteer program allows you to have absolutely no moments of solitude outside of your visits to the bathroom. But on the other hand, having all of those built-in museum partners gives you a great cushion through the emotional bits. We talked, we joked, we helped each other understand the information within the tour. We went shopping along the waterfront once we returned to the mainland. It was easy for me to stay out of my head with my friends there, out of the feelings I could have been having about all that we had seen and heard. Nevertheless, I would soon know the vulnerability, but also the freedom, of museuming alone.

III. And Then

Museuming Together • Museuming Alone

MUSEUMING ALONE

There’s a quote by James Baldwin which says, “To be a Negro in this country and to be relatively conscious, is to be in a rage almost all the time.1" I can’t and won’t speak for all black Americans, but I know that I most certainly relate to this observation. Once I started researching and paying attention to the historic and present systems of white supremacy and capitalism, I couldn’t unsee it all around me. And it all made me furious. I thought constantly of the effects of these systems on the generations of my family, on me, and most of all on my students. They already exhibited the signs of carrying an extra burden on the sole basis of being black and brown. So, this rage that Baldwin speaks of already existed in me before traveling to South Africa. I had, by that point, gotten good at pushing the anger down on a daily basis, knowing that it quietly existed. It was the fire and passion behind my lessons, after all. I think that I was under the naïve impression that it couldn’t burn any brighter, though. I had no idea that it was possible to increase the weight of that terrible burden of anger. Then came solo museuming in Johannesburg.

A view of Jo'Burg from above. I took this on the 50th floor of the Carlton Centre, a former hotel which was the tallest building on the whole continent of Africa until 2019. This attraction is also known as The Top of Africa, and allows tourists a 360-degree view of Johannesburg in its entirety.

I traveled solo from Cape Town to a rather lush hotel in Sandton, Johannesburg, about 2 hours away by plane. By this time, I had been in South Africa for nearly 3 weeks, but it was the most alone I had felt the entire trip. After being surrounded by a gaggle of volunteers for so long, the hotel room felt like Shahara’s Personal And Exclusive Club Med Resort For Shahara And Only Shahara. Did I want to jump up and down, whooping and hollering, on the king-sized bed? Yes, yes I did. However, I settled for room service and local soap operas, which, thank goodness, can be found anywhere in the world.

A week earlier, while booking my flights and hotel in a cute little coffee shop in the suburbs of Cape Town, I had also booked a great deal on an all-day tour guide to show the historic and most significant sights of Johannesburg, pertaining to apartheid. I had no idea how else I would get to all of the places I needed to go in essentially the one day I had there. I assumed I would be with a group of people, which was fine. I could always skip off on my own if needed. However, my tour guide, Beth, arrived at my hotel bright and early the morning after my arrival in Johannesburg and, once I realized I was the only one she would be guiding that day, we were off. This will for sure be a very different museuming experience from my Cape Town visits, I thought. Mercifully, Beth ended up being an amazing asset to my research. She knew so much history and genuinely respected and was excited by my reason for being there, which was much appreciated.

Johannesburg, South Africa. Of course, the fast-food restaurants of America exist in South Africa, too. KFC is HUGE there. I found the idea of being in a foreign city but seeing two restaurants from home next to each other to be hilarious.

Johannesburg was a sight for sore eyes—beautiful brown people were everywhere. I had not experienced this in Cape Town, but here, the familiar movie scene of the hustle and bustle of city life with men and women rushing up and down the sidewalks in suits, cars and cabs honking and driving precariously, people laughing and running up to talk with people they saw and knew, featured an all-black cast of South Africans. I was delighted. I did not expect to be so overjoyed by so simple a thing as the observation of such large numbers of black people being allowed to exist freely in some way.

Beth took me to several important historical places in Johannesburg. But the Apartheid Museum and the Hector Pieterson Museum were the ones that emotionally gutted me. First, we headed to my appointed tour time at the Apartheid Museum. This is a museum that has a reputation for being life-changing. It’s lauded as a museum that everyone should visit whilst in South Africa (it is even ranked top museum of the country). This was the crux of my research travel, as I knew that housed within this museum was the majority of the information I could ever hope to find on apartheid, all in one place.

The Apartheid Museum has a plethora of materials: written information, photographs, artifacts, theater-housed movies, the works. Even spending an entire day within the museum would not be enough time to get through all of the information that is there. Cameras are prohibited inside, which frustrated me, but also forced me to be completely present in my retention of everything I was seeing. In comparison to the copious notes I took at Robben Island, I took only a few notes at the Apartheid Museum because it became so important to absorb everything as I went through the various rooms.

Boooooo. The ‘no photos’ sign outside of the Apartheid Museum’s main building entrance.

All throughout the Apartheid Museum, I struggled to keep my emotions in check externally. There were other patrons in the museum, but because it was a weekday in South Africa’s winter season, I was able to stay relatively alone throughout the whole visit. My rage was quietly present, but painfully so. To see the same things that have happened in America, to my kin, be so closely replicated here in South Africa, to more people who looked like me, my family, and my students was excruciating.

The place it might have hit me most, this painful rage, was in an exhibit which showed a replica of the jail cell where Steve Biko spent his last night (he was murdered by police in jail that night). Patrons are able to stand inside of this jail cell replica, so I did just that. It’s so small, I kept thinking to myself. It is so small. What right did anyone have to do this? To incapacitate a man by conveying that all he is worth is a room the size of a shoebox? My anger suddenly did not seem as quiet and easily controlled as it always had been before. I knew that cameras weren’t allowed, but I took a photo of my face in that jail cell. I wanted to always remember that raw anger in my eyes. I wasn’t used to seeing it there, but I knew it was important that my anger could actually be seen. I was enraged for the rest of my visit. I walked through every exhibit learning more, and adding more fuel to the fire of my rage.

Stepping out of that museum into the bright sunshine at the end of my visit was a shock to my system. Everything that people had said about the Apartheid Museum experience was correct. I already felt changed, felt so much more aware of all of the imbalances of race. But the new additions to my rage came with me, too, and were added to the burden I already carried.

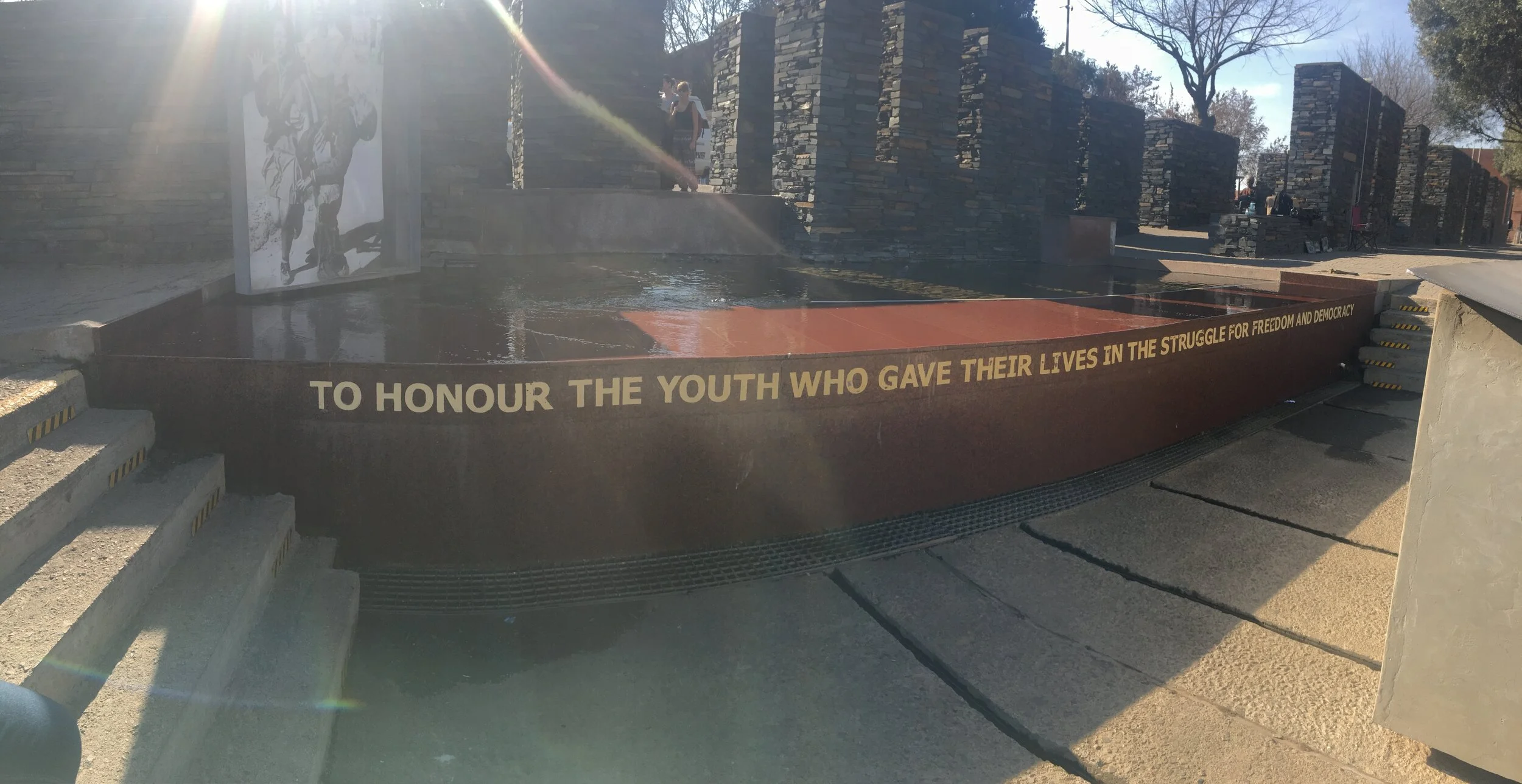

This is the Hector Pieterson Memorial, located in front of the museum. The water represents the tears and blood shed, and the stones of the pillars represent those killed and the stones used as weapons.

Next, we traveled to Soweto (a beautiful and richly historic township in Johannesburg) and after Mandela House and a solo lunch on Vilakazi Street, we ventured to the Hector Pieterson Museum. Beth once again left me at the entrance, with a warning about the emotions I would experience once inside. It’s still difficult for me to talk about that experience. Here is what I can say of that museum and its reason for existing: Hector Pieterson was a child, aged 13, who was shot and killed by police during uprisings in Soweto. Students were peacefully protesting the right to speak their home language in their schools (the colonized language of Afrikaans was being mandated in all schools, causing the local students and teachers alike to struggle). Police were sent in with tear gas and guns. Hector is believed to be one of the first children killed, and there is a poignant photo of him being carried by another student in the aftermath. This photo is portrayed at the memorial site for Hector and all of the youth, which is just two blocks from where Hector was shot. The museum is dedicated to the young people of South Africa who fought against their oppressors (in this case, the police) and were killed. Children. Murdered by police. Final numbers put the death count at around 500 children, who had no weapons until they were shot at first. Then, they began using rocks as a form of self-defense so that they could get away. Rocks versus guns. That phrase kept spinning around inside my head. Rocks versus guns. The Hector Pieterson Museum was last on the schedule for the day, and thank goodness. I could take no more after that. This museum is where I added heavy amounts of grief to the raging burden I held onto.

It felt like I had matured, had aged several years, all in one day. I was overwhelmed but grateful for the knowledge I had received. I spent less than 48 hours in Johannesburg, but those precious moments, both the good ones and the difficult ones, were some of my favorites from my South African trip, or ever.

This is a closeup of the famous photo displayed at the memorial. The boy carrying Hector, Mbuyisa Makhubu, helped to get him to medical care, but it was too late. The girl running with them is Hector’s sister.

I. The Beginning • II. Next

III. And Then•Museuming Together•Museuming Alone

IIII. Both The End and The Beginning

IV. Both The End And The Beginning

I sighed as I walked into yet another exhibit room showing a video, with booming audio, of more black South African children who had been killed in the midst of some part of the uprisings. This room was round, with majorly dimmed lights to allow you to see the often disturbing videos being shown on the curved walls. I felt exhausted—I was suddenly so. very. tired. I was tired of knowing. That burden of what I already knew and had personally experienced of racism combined with all of those graphic visuals of racial violence proved to be too much. So, I sat down on a wooden bench in the middle of the exhibit, and I wept. Once upon a time, I would have cared that at any second anyone could come into this room and see me, a grown woman, clutching a pink and green watermelon-patterned notebook and sobbing. But there wasn’t enough energy left in me to care. And more importantly, why should I?

As a black woman living in America, I find that I’ve always deemed it necessary to be extremely self-aware. This relates to my composure and appearance in public spaces, where it seems there is always someone watching and waiting. Historically, shifts in composure have been problematic for people of color in America. Thus, staying in control of the emotional self is a strategy for remaining under the radar for us. Part of my personal growth in the past few years, then, has been in catering more to myself in these public spaces, and most certainly in museums which speak to oppression towards black people. It is okay if I don’t “have it together,” I realize, because pain is something that shouldn’t have to be hidden from others. It especially shouldn’t be hidden when “others” historically benefit and are protected by the very system which has killed so many of my people. Additionally, I think that it’s particularly important now to show authentic emotion to descendants of oppressors. It’s important to know that pain from the past still hurts in the present, especially when the striker is still a threat.

A sign that, if not for the Afrikaans translation below, could very easily be from the Jim Crow era in the US. This is another artifact from District Six Museum.

I was startled by the fact that there wasn’t much emotion from others at the museums in South Africa I found to be really emotionally-charged. Families walked through exhibits like they were window shopping at the mall, lightly and easily. Individuals read the exhibit information, sometimes shook their heads, and then moved on to the next artifact. There seemed to be so much stoicism present in learning about a horrific history. Perhaps it is partly the job of a museum to also facilitate and encourage response from its patrons. For instance, I appreciated the fact that one civil rights museum I visited in America had open boxes of tissues sitting everywhere throughout the exhibits. It tells the patrons that there is really tough information to be absorbed here, but it needs to be absorbed--and it is okay and normal for you to have a reaction to it.

I am continuing my travel research on systemic racism. Last year I traveled solo by Greyhound bus through a part of my own country that I had never experienced: The South. At the International Civil and Human Rights Museum in Atlanta, I witnessed something that was both surprising and compelling: a pair of older black women weeping loudly together after experiencing the lunch counter exhibit (it is interactive and can be quite triggering). It was the first time I had seen such emotion outside of my own in a museum, particularly post-South Africa. The two ladies continued sobbing as they walked away, over to another exhibit of some other Civil Rights event, and I remembered feeling that I had kind of intruded on them in some way. But also, I had absorbed some of their pain, and it changed the rest of my time there. From that point on, not only was I experiencing these exhibits as myself, a young black American woman, but I was processing these exhibits as they were, as black women of a different generation who recognized and remembered those distinct images and sounds, and remembered what it was like for them, and all they had lost.

I think, though, that this transfer of emotion, this empathy for others is okay and what is to be expected at museums of this nature. If not, it should be expected. The social norms of not emoting in public spaces will not help us to evolve as human beings, or to gain compassion for one another, which is so desperately needed in order for us to survive. Confronting the uncomfortable truths of the past with others is a form of connecting, and in the cases of museums, a way to learn about other individuals and groups--not just the ones on display in the exhibits, but the ones walking and talking all around you.

A quote by Nelson Mandela displayed outside of the Apartheid Museum: “To be free is not merely to cast off one’s chains, but to live in a way that respects and enhances the freedom of others.”

My trip to South Africa was eye-opening for me in so many ways. Of course I learned a wealth of information in regards to my research on apartheid, as was to be expected. I also realized that I enjoyed museuming with others as a way to combat the gloomies that can take hold at historic museums. The other lessons learned and my personal growth through the trip were less anticipated. Any solo trip will strengthen you, as you have to stretch and change within the culture of where you are. The addition of the mentally-trying museums only added to the progress I was able to make emotionally, even if I later had to take time to recover from the trauma of so much emotional weight at once.

The most essential truth of my emotional growth attained during my travels is this: I now know that there is no limit to what I can emotionally endure. The amount of rage and grief I can hold within this body and soul is limitless. Every murder and injustice on a black or brown body increases the weight on my shoulders, but I grow with each wave of grief and anger, and am fortified by the increasing number of ancestors, all so beautiful, black, and proud. I am because they were, and I continue the fight because they cannot.

At Robben Island, the story of a 23-year old man captivated me. His name was Solomon Kalushi Mahlangu and he was an anti-apartheid freedom fighter who was arrested and eventually sentenced to death by hanging. According to those who attended the hanging, Solomon’s last words were, “My blood will nourish the tree that will bear the fruits of freedom. Tell my people I love them. They must continue the fight.” 2 So, that’s what I’m doing. I learn these brutal histories, absorb them and the memories of so many ancestors, and use that passion to teach and write about what has happened so that it cannot happen again. That’s my part of continuing the fight. The desire and need to do so would never have surfaced without my adventures in those South African museums, which will remain forever in my heart's memory.

2. Wall Text, Robben Island Museum, Cape Town, South Africa.

I happened to travel to South Africa the year of Nelson Mandela’s 100th birthday, a widely celebrated event in South Africa. People from all over the world signed this poster with messages of love and gratitude for Mandela. My message said that my students and I would continue to fight the good fight.

“So? What did you think?” Beth asked with a smile as I returned to our rendezvous point at the end of my Apartheid Museum visit. I felt that I resembled a zombie at this point: bloodshot eyes, stumbling around with a vacant, glazed-over expression on my face. I just looked at her. I am sure that my eyes still spoke volumes, but I couldn’t speak. She nodded. We didn’t need to talk about any of it. There was a silent understanding between us. I have so much more work to do, I thought to myself. And this is only the beginning.

I was right about that, too.

Shahara Benson is an educator who has recently officially abandoned the system of education in search of greener (read: more equitable) pastures for children of color. She is incurably curious about all things race and class on an historic, local-to-global scale. Shahara is a reader, writer, and singer who enjoys nature, yoga, and anything sweet. She currently lives in Philadelphia, and likes to travel in her black Converses.